I had recently visited the most recent literature on Video Segmentation and I was startled by how lost I found myself. If you are versed in this field, you are probably familiar with terms such as SVOS, UVOS, VIS, Zero-Shot, One-Shot, etc. If you are not, then you will probably find yourself as lost as I was a few weeks ago.

My main intention was to focus solely on the specific topic I was interested in. This is Video instance Segmentation (VIS), which extends the image instance segmentation task from the image domain to the video domain. The goal is to segment object instances from a predefined category set in videos, then associate the instance identities across frames. It can also be seen as a combination of instance segmentation and object tracking in videos.

As usually I will be trying to update this post with the most recent papers and code implementations I find interesting.

Introduction to Video Segmentation

Video segmentation condenses a lot of different tasks which can have multiple names. I personaly like the taxonomy used in the Youtube-VOS Dataset, which is one of the main benchmarks in this field, so I will stick with it through this post. The different tasks are:

- Video Object Segmentation (VOS): targets at segmenting a particular object instance throughout the entire video sequence given only the object mask of the first frame.

- Video Instance Segmentation (VIS): extends image instance segmentation to videos, aiming to segment and track object instances across frames.

- Referring Video Object Segmentation (RVOS): is a task that requires to segment a particular object instance in a video given a natural language expression that refers to the object instance.

Diagram with the different video segmentation methods

Key concepts

Input sequence length

The input sequence length is crucial in video segmentation. Longer sequences provide more context for accurately segmenting objects, even through occlusions or appearance changes. However, they require more computational power and they cause an increase in training and inference times. Bear in mind that transformers have a quadratic complexity with respect to the sequence length. That’s the reason why most of the models we are going to discuss here are trained with very short clips (mostly between 2 and 8 frames).

Stride

The input sequence length defines the number of frames processed in parallel. The stride is the one that determines the temporal distance between adjacent frames in the input sequence. A stride of 1 means that the input sequence is a continuous sequence of frames, while a stride of 2 means that every other frame is skipped. By increasing the stride, the system can work faster because even though it will be looking at the same amount of frames at once, it will need to process fewer frames in total.

Offline vs Online

Many video segmentation approaches are categorized as offline. They process the entire video in one go, which is ideal for short videos and limited by the maximum length the model can process. On the other hand online methods divide videos into overlapping chunks, and results from these segments are merged using a rule-based post-tracking method. This approach ensures continuous tracking across the video by processing and linking instances from overlapping segments.

Video Instance Segmentation

From now on I will exclusively focus on Video Instance Segmentation (VIS). Most papers before 2020 were based on either:

- Top-down approach: following tracking-by-detection methods (you can check this other post for more information on this topic)

- Bottom-up approach: clustering pixel embeddings into objects.

These method suffered from different issues, and around 2020, transformer-based approaches began to appear. Most of the research focused on how to throw a transformer into this problem that could hold up to the state-of-the-art.

Datasets

The most common dataset used for VIS is called YouTube-VIS. It comprises three different versions:

- YouTube-VIS-2019: 2,883 high-resolution YouTube videos with 40 object categories. Longest video is 1,000 frames. Longest video only contains 36 frames so it is easy to execute on offline mode.

- YouTube-VIS-2021: 3,859 high-resolution YouTube video with an improved 40-category label set by merging some and adding new ones. Longer video lengths force to use a near-online approach.

- YouTube-VIS-2022: not considered in this post since it is more recent than the papers that are covered.

The following table summarizes the papers I will be discussing in this post and its performance on the YouTube-VIS-2019 dataset.

| Method | Backbone | MST | FPS | AP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VisTR | ResNet-50 | ❌ | 51.1 | 36.2 |

| VisTR | ResNet-101 | ❌ | 43.5 | 40.1 |

| IFC | ResNet-50 | ✅ | 107.1 | 41.2 |

| IFC | ResNet-101 | ✅ | 89.4 | 42.6 |

| TeViT | MsgShifT | ❌ | 68.9 | 45.9 |

| TeViT | MsgShifT | ✅ | 68.9 | 46.6 |

Table 1. Comparisons on YouTube-VIS-2019 dataset from TeViT paper [5]. MST indicates multi-scale training strategy. FPS measured with a single TESLA V100. Note all methods used offline evaluation for reporting metrics.

Note the differences in precision when comparing with the reported results in Youtube-VIS-2021 dataset. This is due to the increase in video sizes, which forces the model to work in online mode, processing chunks of the video that then need to be merged.

| Method | Backbone | AP |

|---|---|---|

| IFC | ResNet-101 | 35.2 (36.6 reported in [4]) |

| TeViT | MsgShifT | 37.9 |

Table 2. Comparisons on YouTube-VIS-2021 dataset from TeViT paper [5].

VisTR (2021)

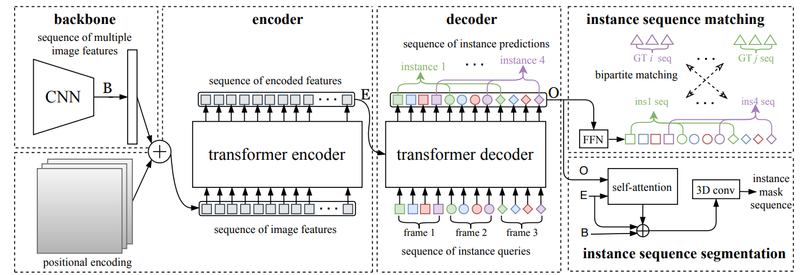

VisTR, short for VIS Transformer, emerged as one of the initial transformer-based VIS methods to achieve notable accuracy on the YouTube-VIS dataset, thanks to an effective adaptation of DETR [2] for segmentation. This framework processes a fixed sequence of video frames using a ResNet backbone to independently extract features from each image. These extracted features are then concatenated, enriched with a 3D positional encoding, and injected into an encoder-decoder transformer architecture, which outputs a sequence of object predictions in order.

VisTR architecture diagram

Key ideas we need to highlight about this method:

- Instance queries are fixed, learnable parameters that determine the number of instances that can be predicted (input of decoder in the diagram).

- Training involves instance sequence prediction over

- The Hungarian algorithm is used to find a bipartite matching between ground-truth and prediction (as in DETR [2]).

- Solving 3 using masks is very expensive. A module is added to obtain bounding boxes from instance predictions and solve the matching efficiently.

- The loss consists on a combination of the bounding box, the mask and the class prediction errors.

- A 3D conv module fuses temporal information before masks are obtained.

Drawbacks: The models are trained on 8 V100 GPUs of 32G RAM, with 1 video clip per GPU. Either low resolution or short clips are used to fit in memory. VisTR remains as a complete offline strategy because it takes the entire video as an input (from IFC paper).

IFC

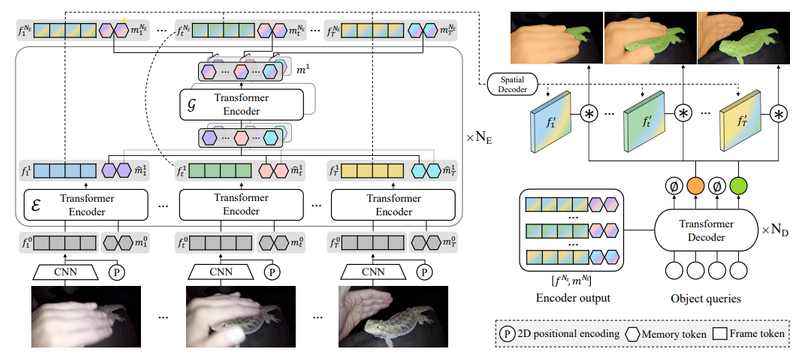

Inter-frame Communication Transformers (IFC) leverages the idea that, since humans can summarize scenes briefly and consecutive frames often share similarities, it’s feasible to communicate frame differences with minimal data. To reduce computational load, IFC utilizes a number of ‘memory tokens’ to exchange information between frames, thus lowering the complexity of space-time attention.

IFC architecture diagram

The architecture integrates Transformer encoders with ResNet feature maps and learnable memory tokens. Encoder blocks are composed of:

- Encode-Receive (

- Gather-Communicate (

The decoder used a fixed number of object queries (

- A class head for class probability distribution of instances

- A segmentation head producing

Loss calculation also follows DETR incorporating the Hungarian algorithm, applying it directly to the masks.

TeViT

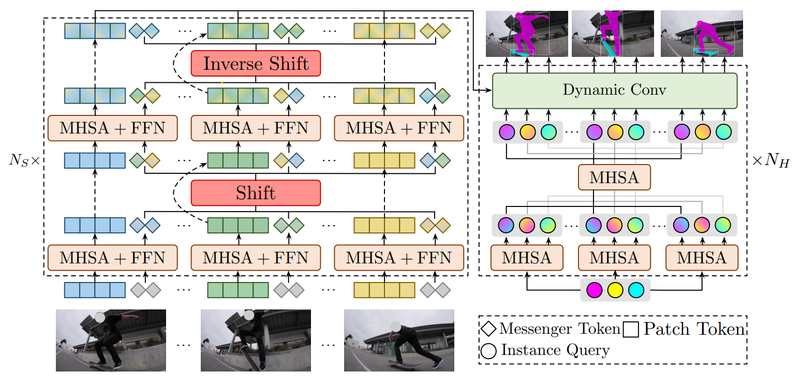

The Temporally Efficient Vision Transformer (TeViT) advances the ideas from IFC by using fewer parameters to fuse information across video frames and including a fully transformer backbone. It also introduces minor improvements in its head stage for more efficient processing.

TeViT architecture diagram

At its core, TeViT employs a pyramid vision transformer [6] structure and innovates by replacing IFC’s memory tokens with temporal messenger tokens. These tokens are periodically shifted along the temporal axis within each block to merge information from distinct frames. This shift operation is straightforward, yet remarkably effective, adding no extra parameters to the system.

The head implementation emphasizes modeling temporal relations at the instance level, drawing on the principles of QueryInst [7]. As illustrated in the diagram, the same instance queries are initially applied across every frame. These queries are processed through a parameter-shared multi-head self-attention (MHSA) mechanism and a dynamic convolutional layer [8], which integrates the data with instance region features from the backbone. Finally, task-specific heads (such as classification, box, and mask heads) generate predictions for a sequence of video instances.

The loss computation incorporates the Hungarian algorithm alongside a combination of box, mask, and class prediction errors (details provided in the paper).

Conclusion

Exploring the literature around video instance segmentation (VIS) has been a fun experience. Transformers are now showing up in most of the research in this area. It is quite fascinating to observe ongoing efforts aimed at reducing the complexities associated with video processing, such as minimizing the number of parameters needed to merge time-related features effectively. The influence of the DETR paper on all the methods discussed is also noteworthy.

I will keep updating this post with new and relevant research findings. Feel free to share your thoughts in the comments below or suggest any papers you would like me to explore next.

References

- [1] Yang, L., Fan, Y., & Xu, N. (2019). Video instance segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (pp. 5188-5197).

- [2] Wang, Y., Xu, Z., Wang, X., Shen, C., Cheng, B., Shen, H., & Xia, H. (2021). End-to-end video instance segmentation with transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (pp. 8741-8750).

- [3] Carion, N., Massa, F., Synnaeve, G., Usunier, N., Kirillov, A., & Zagoruyko, S. (2020, August). End-to-end object detection with transformers. In European conference on computer vision (pp. 213-229). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- [4] Hwang, S., Heo, M., Oh, S. W., & Kim, S. J. (2021). Video instance segmentation using inter-frame communication transformers. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 34, 13352-13363.

- [5] Yang, S., Wang, X., Li, Y., Fang, Y., Fang, J., Liu, W., … & Shan, Y. (2022). Temporally efficient vision transformer for video instance segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (pp. 2885-2895).

- [6] Wang, W., Xie, E., Li, X., Fan, D. P., Song, K., Liang, D., … & Shao, L. (2021). Pyramid vision transformer: A versatile backbone for dense prediction without convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision (pp. 568-578).

- [7] Fang, Y., Yang, S., Wang, X., Li, Y., Fang, C., Shan, Y., … & Liu, W. (2021). Instances as queries. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision (pp. 6910-6919).

- [8] Chen, Y., Dai, X., Liu, M., Chen, D., Yuan, L., & Liu, Z. (2020). Dynamic convolution: Attention over convolution kernels. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (pp. 11030-11039).